|

|||||

|

Sunday, December 27, 1959

|

Welcome

to the official website of Memphis, Tennessee!

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

MAIN STREET, MEMPHIS, 1951. |

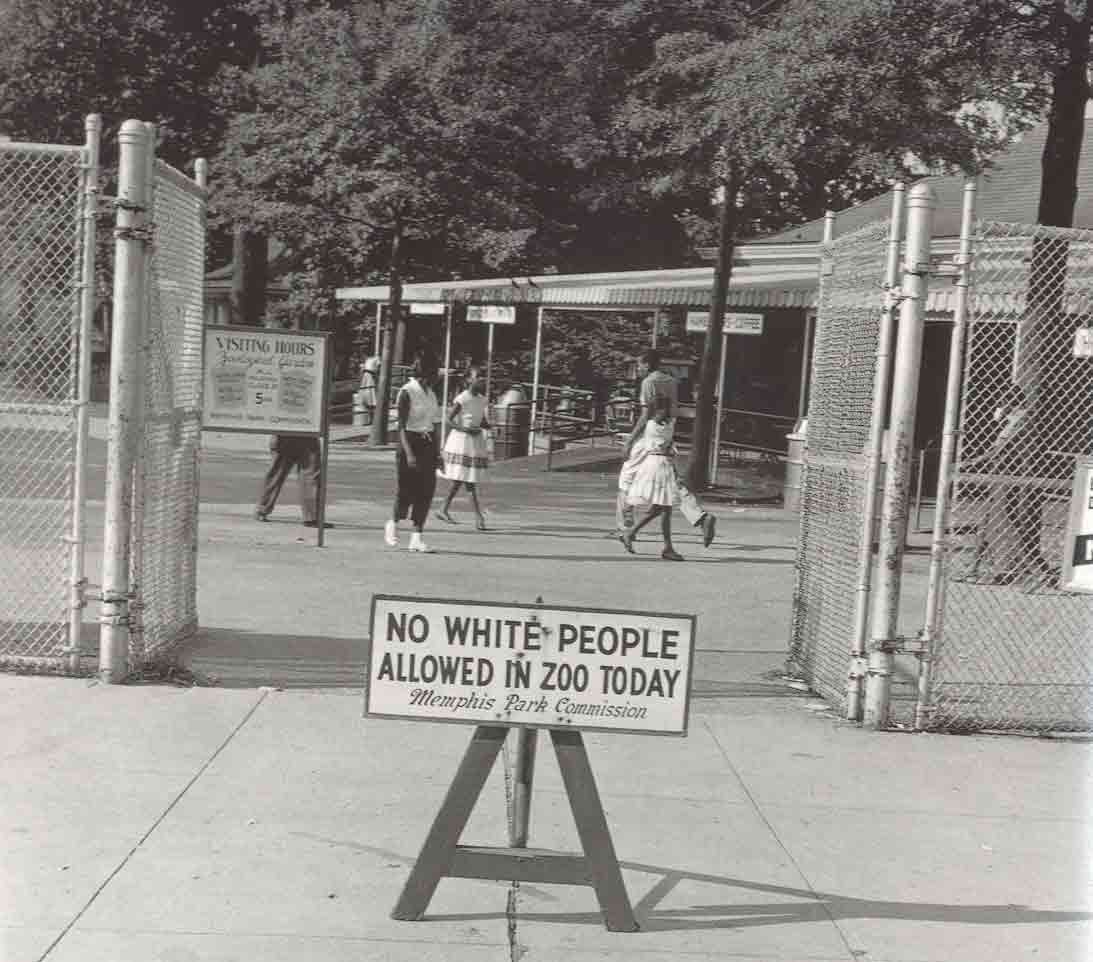

Before Birmingham: The Early Stages of the Civil Rights Struggle in Memphis Imagine Memphis in the 1950's Before Martin Luther King was a household name Before Graceland was a cultural mecca Before the very image of "The South" conjured up images of police in riot gear, massive demonstrations, and a struggle to assert basic human freedoms Before Memphis had a pyramid, a Liberty Bowl, and a FedEx superhub When "East Memphis" was only a few blocks from downtown Memphis, Tennessee, as it existed in the 1950, was anything but memorable. True, local battles were waged over expressway construction and municipal annexation, but for the most part Memphians were just like those in every other American city in the 1950's. They bought bigger cars, more appliances, and tried to live "the good life." Memphians flocked to the suburbs in record numbers in the 1950's, and city growth far exceeded prewar estimates. Memphis was a genteel city, with its fortunes built upon King Cotton and its peripheral industries, and its people thought of themselves as a progressive, forward-thinking sort. But underneath the surface, a volcano was waiting to erupt. The civil rights struggle of the 1960's was a direct outcome of the brewing tensions of the previous decade. For a people who grew up in these unsettled times of racial strife, McCarthyism, and the threat of atomic war, the 1950's produced a climate open to social change. Memphis in the 1950's was, for the most part, two distinct cities: Black Memphis and White Memphis. Subject to the humiliation of Jim Crowism, blacks in Memphis were forced to create their own community, with its symbolic capital as Beale Street. When they dared to enter White Memphis, blacks were met with a world that deemed them inferior, exposing them to segregated facilities and a nearly zero chance of employment opportunities above the level of janitor. In the 1950's, most black males worked as operatives, laborers, and service workers, while black females worked mostly as domestics. During this period, the NAACP actively fought to desegregate the city's highly segregated institutions, including parks, swimming pools, and golf courses. Suits were filed in 1956 and 1957 to open up the city's buses and libraries to persons of all races. The Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision by the U.S. Supreme court to desegregate was handed down in 1954, but Memphis was very slow to react. The court said that desegregation should take place "with all deliberate speed," so Memphis City School Board officials took over 6 years before the first integrated classes met in 1961. The struggle for civil rights began to take off in the city in the early 1960's with sit-ins and protests, but Memphis, however, escaped widespread violence. Because of this, the city remained out of the spotlight - while other cities like Montgomery, Birmingham, and Atlanta were literally torn apart. Why is this so? Maxine Smith, a Memphis civil rights activist, gives said the answer was twofold:

Another factor, according to Smith, was the conduct of Police Commissioner Claude Armour. A self-proclaimed segregationist, he was also a 'professionalist,' and helped to create a calmer atmosphere than in most cities. While Memphis did not erupt into full-scale violence in the 1950's, the stage was nonetheless set for a showdown between the Old Guard and the progressive forces sweeping the country |

||||||||

|

(Click on picture to enlarge)

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

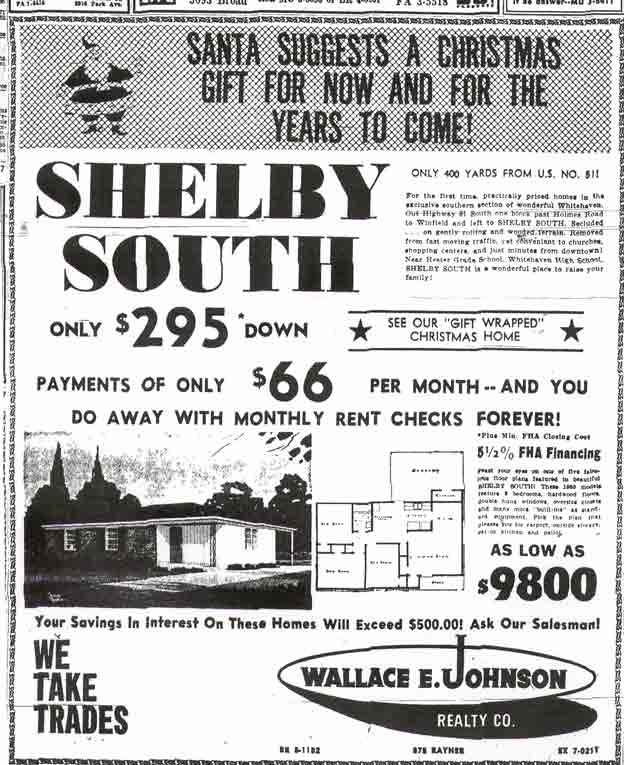

AN EXAMPLE OF THE AVAILABILITY OF AFFORDABLE SUBURBAN HOUSING IN MEMPHIS, 1952. |

|||||||||

|

CLUB PARADISE, MEMPHIS, 1950s. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

SAME NEWSPAPER ASKING FOR "WHITE BLOOD DONORS", 1955. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

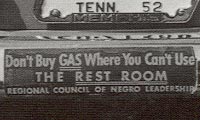

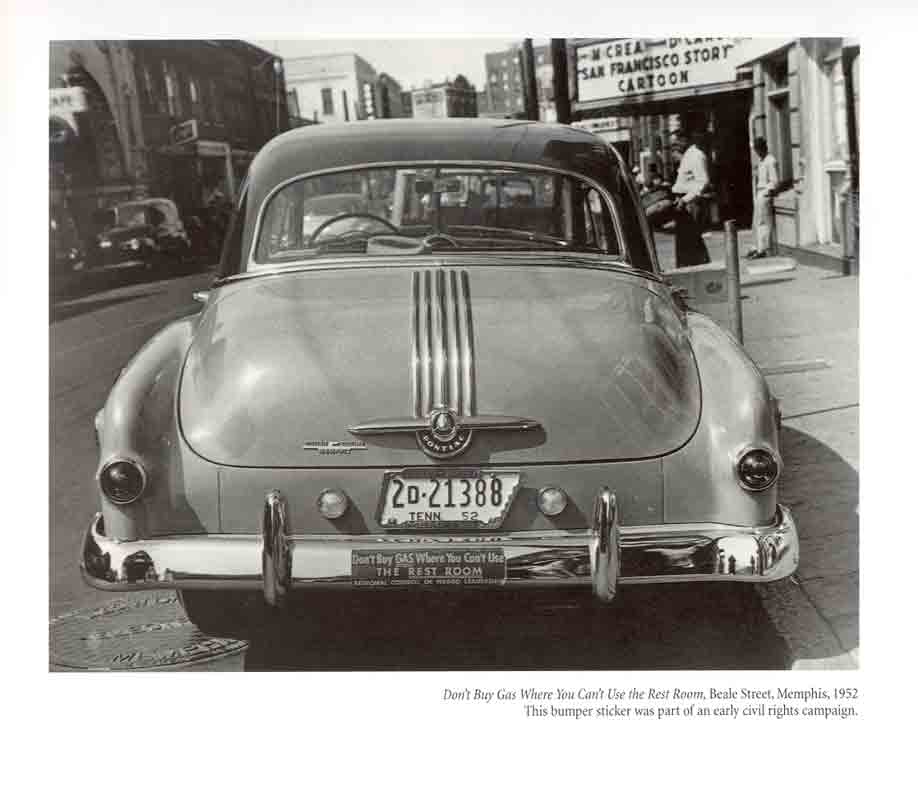

QUIET SOCIAL PROTEST, 1952. |

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

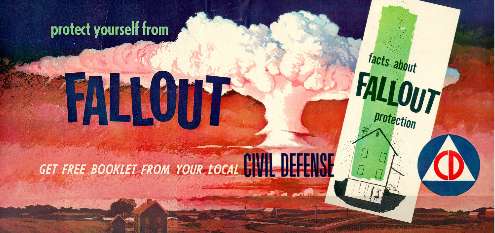

MEMPHIANS STILL HAD TIME TO PREPARE FOR NUCLEAR ANNIHILATION |

|||||||||

|

Copyright, 1959. The City of Memphis, Tennessee. For Individual Citations, Click HERE |

|||||||||